Recent Posts

What’s Wrong with Bananas

Reproductively, domesticated banana plants are self-copying machines. Proto-farmers who found an individual whose fruit they liked (maybe tasty and not so seedy) could dig up its suckers and replant them in a nearby clearing or even along the trail. In a few years, an industrious proto-farmer might …

Remembering When Americans Picnicked in Cemeteries

WITHIN THE IRON-WROUGHT WALLS OF American cemeteries—beneath the shade of oak trees and tombs’ stoic penumbras—you could say many people “rest in peace.” However, not so long ago, people of the still-breathing sort gathered in graveyards to rest, and dine, in peace.

During the 19th century, and especially in its later years, snacking in cemeteries happened across the United States. It wasn’t just apple-munching alongside the winding avenues of graveyards. Since many municipalities still lacked proper recreational areas, many people had full-blown picnics in their local cemeteries. The tombstone-laden fields were the closest things, then, to modern-day public parks.

In Dayton, Ohio, for instance, Victorian-era women wielded parasols as they promenaded through mass assemblages at Woodland Cemetery, en route to luncheon on their family lots. Meanwhile, New Yorkers strolled through Saint Paul’s Churchyard in Lower Manhattan, bearing baskets filled with fruits, ginger snaps, and beef sandwiches.

One of the reasons why eating in cemeteries become a “fad,” as some reporters called it, was that epidemics were raging across the country: Yellow fever and cholera flourished, children passed away before turning 10, women died during childbirth. Death was a constant visitor for many families, and in cemeteries, people could “talk” and break bread with family and friends, both living and deceased.

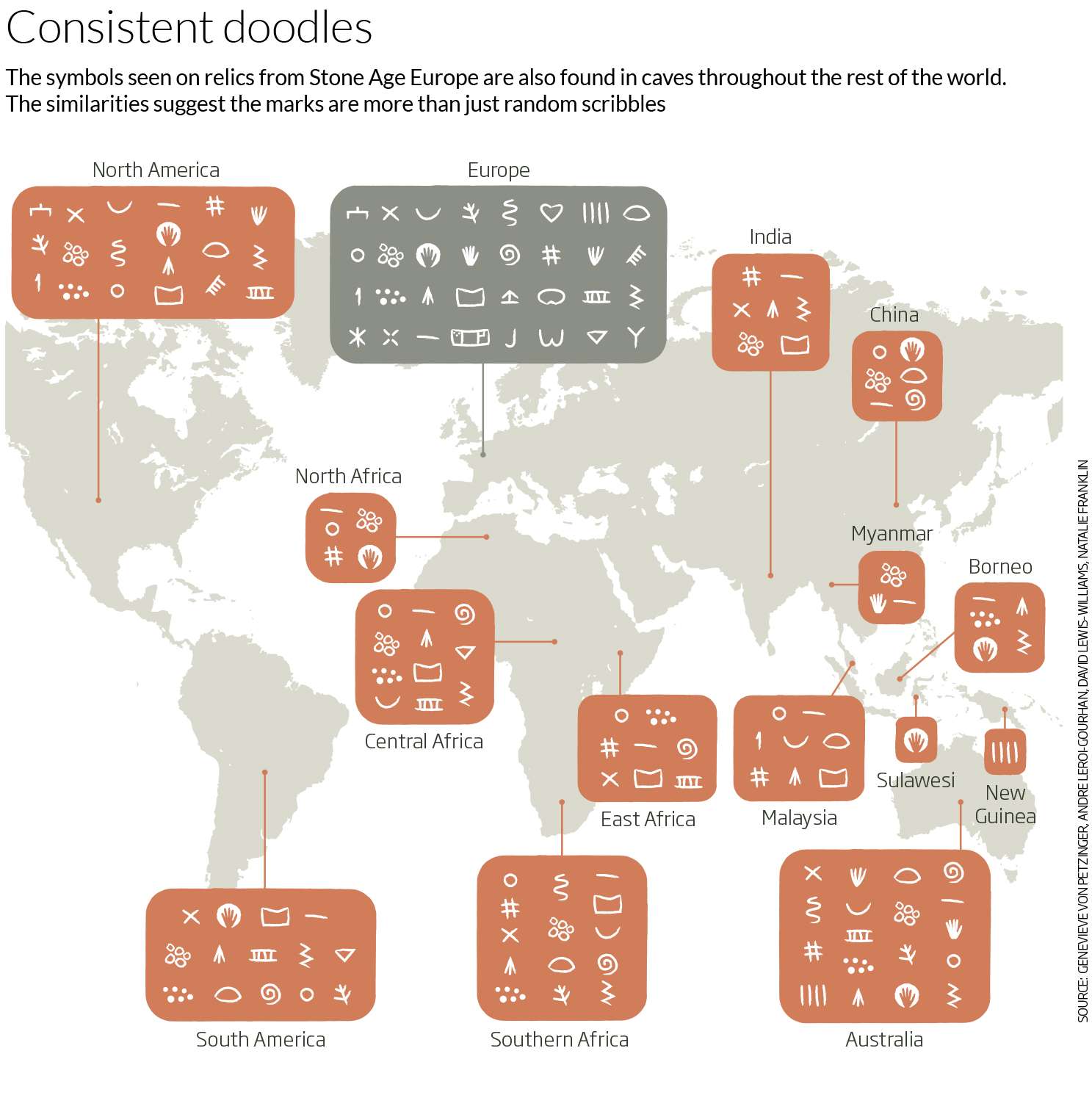

Code hidden in Stone Age art may be the root of human writing

When she first saw the necklace, Genevieve von Petzinger feared the trip halfway around the globe to the French village of Les Eyzies-de-Tayac had been in vain. The dozens of ancient deer teeth laid out before her, each one pierced like a bead, looked roughly the same. It was only when she flipped one over that the hairs on the back of her neck stood up. On the reverse were three etched symbols: a line, an X and another line.

Von Petzinger, a palaeoanthropologist from the University of Victoria in Canada, is spearheading an unusual study of cave art. Her interest lies not in the breathtaking paintings of bulls, horses and bison that usually spring to mind, but in the smaller, geometric symbols frequently found alongside them. Her work has convinced her that far from being random doodles, the simple shapes represent a fundamental shift in our ancestors’ mental skills.

The first formal writing system that we know of is the 5000-year-old cuneiform script of the ancient city of Uruk in what is now Iraq. But it and other systems like it – such as Egyptian hieroglyphs – are complex and didn’t emerge from a vacuum. There must have been an earlier time when people first started playing with simple abstract signs. For years, von Petzinger has wondered if the circles, triangles and squiggles that humans began leaving on cave walls 40,000 years ago represent that special time in our history – the creation of the first human code.

If so, the marks are not to be sniffed at. Our ability to represent a concept with an abstract sign is something no other animal, not even our closest cousins the chimpanzees, can do. It is arguably also the foundation for our advanced, global culture.

Bunny Rescue

The world is a great network of beings who at their core care about each other.